DISPATCHES

Wilfred Bion, one of the 20th century’s great thinkers on the human psyche, and who as a young man served as a British tank commander in the First World War, once wrote: “In war, the enemy’s object is so to terrify you that you cannot think clearly, while your object is to continue to think clearly, no matter how adverse or frightening the situation.” Bion’s words resonated when I came across them earlier this year.

Since late January, a good deal of federal conservation funding has been frozen, released, cut, repurposed, or simply vanished. The inconsistent presence of reason, or in many cases even information, has compounded the disruption. Anecdotes I have come across include these:

- Some have had Urban Forest Funding frozen, then at least outstanding invoices paid.

- Many RCPPs have been paused or cancelled.

- The Climate Smart Commodities Program is begin completely refashioned, funding for Black farmers cut.

- The Park Service’s Outdoor Recreation Legacy Program website reportedly disappeared, staff have been reassigned, prior email and phone communication links disabled.

- Some two thousand seasonal wildfire workers were fired.

- Field offices in some agencies are threatened with consolidation, a move to force retirements and resignations.

- People are being fired from the Forest Service, Natural Resources Conservation Service, the United States Geological Survey, and other agencies.

- USAID is being shuttered.

Of those who have not been fired, many people with years of service to the public, deep expertise, and invaluable knowledge about how to get things done are retiring or leaving federal employment. Many of those who remain are uneasy at the least.

Emotional turbulence has accompanied funding and functional turmoil. Things conservationists have worked to accomplish for years are being damaged or discontinued or placed in doubt. Colleagues and friends in federal service – dedicated people – are being disrespected and discarded. The programs of some conservation nonprofits are threatened. A few may not survive the year. Many conservation practitioners and leaders face difficult decisions and extraordinary stress. Anxiety has diffused across the field. “What did we do to deserve this?” people wonder. What’s next?

Responses run the gamut. Many organizations are adapting instinctively. While not changing their mission, some are changing outward-facing language and scaling back associations that they believe could pose risks to their federal funding. Many with signed agreements and appropriated funds are proceeding with work apace, prepared to protect these resources in court if necessary. Others are choosing not to contest cancellations. Some are furloughing staff. Others are looking to expand their state and local activity. Many are drawing upon shared information sources and networks for news and support.

Slowly, some organizations across the tiny conservation field are recognizing common cause and beginning to band together. Broader legal actions are coalescing in places. Here and there, groups and funders are meeting to begin to develop ideas for novel approaches in areas from which the federal government is being removed.

Some are finding a way to look a few steps ahead. Scenario planning is the most common activity among them. This includes the scenario of how they will continue to preserve their mission with little or no federal funding for the next several years. Even as they think through contingencies and retrench where unavoidable, a subset of these groups are sustaining an unflinching focus on possibilities, generating opportunities, pressing forward.

STRATEGIES FOR FUNDERS (and others)

Some funders have hit things spot on. It seems that many are lagging practitioners in thought and action in response to the situation. They seem still dazed by it all. As more and more funders regain perspective and momentum, several field-needs, among many, deserve mention for consideration.

1. Triage.

• Make existing grants flexible that are contingent on or matches to federal funding. Let groups use these funds to keep work moving, regroup and strategize, seek advocacy and legal advice, even to pursue legal work to retain or obtain legally due federal monies, and other activities groups may propose.

• Either with flexed grants or new loan funds, bridge frozen or delayed payments on federal contracts. For a time, be prepared to convert any loans to grants.

• Create federal advocacy capacity to advise large sets of related NGOs on how to address situations with federal funds, e.g., laying out a path, helping arrange meetings with members of congress or agencies, etc.

• Strengthen and replicate existing information and professional networks. A very incomplete set of reference points include:

- Great information on EPA and other agency funding by former EPA insiders. (Environmental Protection Network)

- Excellent statewide digest of conservation and environment developments for Pennsylvania by Dave Hess, the former DEP Secretary. Every state should have one of these. (Pennsylvania Environmental Digest)

- A terrific clearinghouse of information on impacts and opportunities by Dãnia Davy. (Land & Liberation.com)

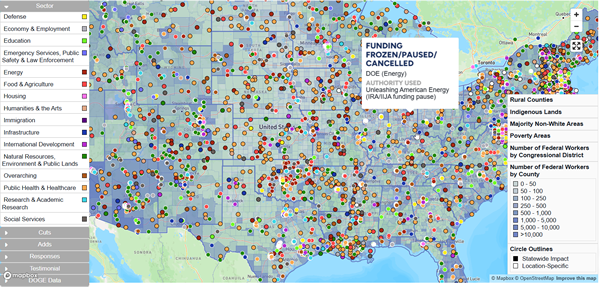

- An interactive map from The Impact Project keeping track of funding impacts. (The Impact Project)

• Fund a range of exercises to generate thinking about where there may be opportunity in crisis.

2. Foster wellbeing.

Check in with your grantees. Encourage them to make time for reflection and care. Demonstrate your support by funding combinations of time, space, and professional expertise organizations need to vent, find support and balance, regroup, and refresh.

3. Think ahead.

On balance the field is reacting to immediate crises and optimizing for the short term, understandably. This is playing catch-up. You and your grantees need to get ahead of things. Funders need to help the field anticipate bigger, broader challenges.

- If you are not already doing so, move expeditiously to anticipate how debates over the FY 2026 federal budget may play out. More broadly, there are some signs that what is happening now is an early expression of a general attack on civil society – especially NGOs and their private funders – that could well take clearer form in months to come. Perhaps there will be even more funding cuts and even challenges to your tax-exempt status. Research, scenario plan, get prepared.

- Press organizations across the field – both larger groups and smaller groups, nationally and locally – to band together. (And funders need to do this among themselves, too.) Pushing back, whether within one field or across many, rests on resources and public voice. This can only result – meaningfully – from institutions banding together.

TOUCHSTONES

The conservation field is continuously refueled by the many tangible results it regularly produces. Good things beget good things. Practical, even groundbreaking innovations beget replications. Mission-ideation fuels pragmatic action, which fuels belief, which fuels ideation. Do we need to remind ourselves of this just now? I don’t know. What I can say is that when I recently reviewed a folder of accumulated conservation news gleanings as I began to consider the content for this newsletter, I found a measure of &emdash; I am not sure what to call it. Maybe reconfirmed purpose? &emdash; in the robustness, relevance, and vitality in the stories.

➤ Maryland recently reached its goal of preserving 30 percent of the state’s land base. It is setting its sights on 40 percent. Whether to conserve wildlife habitat, preserve farm and ranchlands, improve water quality, buffer military bases, sequester carbon, or just keep open spaces open, most people see many reasons to protect land, whatever their political leanings may be.

➤ Last fall, with the support of nearly 6 in 10 voters, Everett, Washington, passed a city ballot measure ensuring the right of the Snohomish River “to exist, regenerate and flourish” within the city’s boundaries, giving this segment of the river legal standing. In Everett, a coalition of developers and businesses sued to block the measure’s implementation.

What strikes me here is not necessarily this specific effort but the creativity of the field, the eagerness to think, to push conceptual and practical boundaries. Some creative approaches succeed, others don’t, at least not immediately. But all of this work helps spark an ongoing dialogue about our greater responsibilities. It makes all of us better.

➤ A mile of beach on the Rockaway Peninsula here in New York City is closed a good part of each spring and summer so that an endangered shorebird, the coastal piping plover, can nest. In 2023, there were 13 nesting pairs on this stretch of sand. Nine years earlier there were 8 pairs. The work of recovery is hard. Beach closure is an effective component of it.

A large proportion of the local population struggles economically. Many residents are not happy with the beach closure. Some say opening it would increase economic opportunities. “We are an endangered species, too,” the local city councilwoman was quoted as saying in a news story. “Where’s our protection?”

Conservationists understand better than they did in the past the need to hear people out, work across difference, hold multiple truths in mind, help everyone thrive. The field has made progress on this. More work remains. And yet it is important to be clear-headed when presented with misdirected animus and solutions.

A basic principle remains vital and bears reassertion. Generating an increment of human wellbeing of unknown amount and duration by destroying a piece of nature for all time is an ethical failure, diminishes us as humans, and weakens the complexity of interaction on which all life depends.

➤ The young continue to inspire. Two recent cases in point.

One is the students of the Green Initiative, a club at a Montana high school. Under their state constitution, all Montanans have a right to a healthy environment. The students joined Held v. Montana, a suit that pressed the state to help fulfil this constitutional promise by including the assessment of climate impacts in state environmental reviews. Last December, the Montana State Supreme Court ruled in favor of the students and their co-plaintiffs. Resistance to the ruling quickly emerged from the fossil fuel industry, the legislature, and the governor. But the students plan to keep fighting, opening new pathways.

Another case is the work of young Native Americans in Alaska organizing fights against road building, open-pit mining, and industrial fishing that harm wildlife and ways of life. These young people are confronting the hard work of abating our ongoing damage to our climate and the natural world. They are as clear-headed as can be. “What I do today affects tomorrow,” said a young Alaskan woman. “It’s the whole reason I got into this work.”

Yep.

RETURN

The rats’ affront left me feeling powerless and dispirited. They had burrowed in by the two trash cans we provide visitors to the community garden, and just at the edge of the sidewalk by the trash can the city provides on the corner. Regular maintenance of bait stations along the fence by the Sanitation Department tamped down their numbers, but the exceptionally clever rodents endure. They began eating smaller plants. And now I noticed coneflower leaves disappearing one by one. I tried a number of different sprays and other tactics. But in a few weeks the echinacea was gone.

Still, thought and desire kept churning, and then anger roused me from helplessness and reignited my instinct for possibilities. I ordered some Joe Pye weed and a couple of other plants that have proven resilient, and I brought in the Marines: common milkweed. So far, so good.

As I may have mentioned at some point, I grew up in Maryland taking care of our near-acre yard. Part of its vegetative wonder was the azaleas, some ninety of them. Six or seven years ago, I planted three azaleas in the community garden and delighted at their blooms each spring. But over time I was no longer able to ignore clear signs of decline. They should have been three times their size. Instead they were shrinking. I had the soil tested, was more rigorous with fertilizer. Nothing worked.

I deferred what I knew needed to be tried because of the risk. But, their progress toward disaster, whether pest, disease, or location, was moving them there, was obvious. So on a bright day last spring, just after the last of their few flowers fell, I transplanted them to an area where I could keep a more regular eye on them, and then I cut them down to near the ground. There they sat, barren and dazed, for interminable weeks.

And then earlier this spring, as the garden does so patiently again and again, the azaleas taught me about the importance of persistence, the value of space to regroup, and the enduring truth – at times with our helping hand – of nature’s renewing force.

Do you have reactions or thoughts about any of the themes in this piece? Shoot me an email here or use my contact page.

IMAGES: Students photo: Louise Johns/High Country News. Used by permission. Map: The Impact Project. All other photos are by Peter Szabo.