Nature Conservation Works

So says a landmark study recently published in Science. (Click here for a link to the article.) This is powerful news, and it should be a heartening boost for everyone who has committed their work and funding to nature, as well as anyone considering whether to do so.

The results come from the first broad-based meta-analysis of the simple question of whether conservation action has an impact on biodiversity. The authors examined 186 studies produced around the world over the last hundred years and concluded that across different timeframes, different scales, different geographies, and different tactics:

In 66% of the cases examined, biodiversity improved more or declined less than if no action had been taken. In terms of specific actions:

- The largest effects were produced by invasive species control and management.

- This was followed by two things: efforts to reduce habitat loss and degradation through policy change or restoration; and sustainable management of ecosystems.

- Protected areas also had a positive effect on biodiversity outcomes.

Great gaps remain in the conservation of nature. Much more work is needed in many more places. Globally, according to the report in Science, funding needs to be at least doubled and probably tripled (along with the capacity to put it to effective use).

The significant learning from this research is that – broadly speaking – investments of financial resources and professional capacity in conservation action pay off. We need to continue to evolve the frames of mind that currently inhibit the flow of money and capacity to this essential aim. This seminal study should help.

[For more information on the study, see the press release out of the Global Environmental Facility.]

Think Again

As I began to prepare this newsletter I thought I might write something about learning in organizations. I have been seeing the word “learning” appear with increasing frequency in department and job titles, workshop names, RFPs, journal articles, and elsewhere. Words do have their moments. But I also think language expresses something deeper that is going on, often not quite conscious, in organizations, fields, society. So what is going on here? I began to wonder.

Quickly I found myself overwhelmed and lost. I filled the margins of my printouts of Mark K. Smith’s excellent summaries of the works of Peter Senge and Donald Schon with affirmations, sarcasm, critiques, and questions. The pages became so full that when I returned later to these and other documents I had read they made less sense to me, not more.

Senge’s The Fifth Discipline, his great exposition on the learning organization, has sold a million copies, and one might conclude from this that the question had been adequately addressed. But still, organizational learning frameworks continue to pour forth.

For the most part, all of this is a good thing – the foregrounding of the word “learning,” the frameworks. Organizations must learn well to adapt and thrive. Leaders should have some sense of how to foster learning in their institutions.

Yet something feels unsettled in the flood of concepts and the naming. It is almost as if, perhaps to overstate, there is in them a kind of defense against learning. For instance, the great energy (and often no small amount of ego) poured into theories of change – those seeming building blocks of organizational learning – too often depletes the drive to revisit them, let alone to use them well. Indeed, it could be argued that the ToC tool itself is actually a kind of diversion from the learning process. At a higher level, “systems thinking” remains vague almost to the point of uselessness, but still it retains a kind of haughty authority to which we defer. Can we point to many outstanding examples of “learning organizations”? Why is that presented as an unquestioned good end in itself? Who gets to decide when to learn, what to learn, how to learn in organizations? And, in this context, what do we mean by learning anyway?

Welcome to my marginalia.

Any good manager will tell you that learning is not always necessary, even as they will also say that this does not mean it is unimportant. When it is necessary, it is vital. There are times when the preponderance of concern needs to go toward action, and there are periods when thinking should predominate.

As I wrote that, it emerged, an answer of a sort: thinking. There can be no learning without thinking. It is a precondition. We take thinking for granted, but I’d say (with some exaggeration that I hope will provoke the reader) that thinking is relatively rare in organizational life.

Having observed many organizations it seems to me that one factor, among a number of important ones, contributes most to fostering thinking: an adequate comfort with uncertainty. If this comfort is insufficient, anxiety reigns supreme (it is, of course, always present in the learning process), thinking atrophies, and the learning process becomes a rote, zombie habit.

Comfort with uncertainty is of singular value because it enables two things that are necessary for healthy thinking. One is an openness to taking in all relevant information, whether or not it conforms to expectations or desires. The other is a supple, deliberative process of making meaning from that information.

The rest, as they say, is commentary.

Seeds of Change

A recent article in High Country News offered a mind-expanding, spirit-lifting story of the power of seeds. Looking at cases of restoration across prairies, estuaries, wetlands, and sand dunes, reporter Josephine Woolington recounts how Indigenous knowledge, ecological science, volunteer grunt-work, and patience unleash the revitalizing power of recovery that lives in native plant seeds, even those long buried by careless alterations of the land.

I was particularly struck by the efforts of the Yakama Nation to restore their lands, beginning with a 400-acre former barley field along Toppenish Creek. Traditional knowledge of water flows, imparted to project biologists by tribal elders, helped foster a return of tule, willow, and wapato, absent from the reservation since settlers converted the wetlands to farms early in the last century.

The approach on the Yakama, honed over more than two decades and now thousands of acres, was pared back and attentive. “Bring back the water, control the weeds, and see what happens,” summarizes Woolington.

Reading this piece brought to mind Aldo Leopold’s maxim: “Anything is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” As I considered this, a notion surfaced. Today, in a world even more drastically transformed by human hands than when he penned the phrase some 80 years ago, we might say with equal truth that a thing is right when it tends to restore the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. We know it is wrong when it tends otherwise.

The roots of restoration lie not only in the seeds but in ourselves. The flourishing of the restorative instinct – a powerful instinct for care each of us possesses – rests in great part on a reorientation, even a reconceptualization, of our relationship to the land, to nature. Learning. Relationship. These seem fundamental. Relationships are at heart emotional things.

Concepts and Care

“Oh my!” a sandpapery voice remarks from beyond the wrought iron fence. “I remember this place from thirty years ago.”

I am kicking a shovel in a tight circle around a privet that needs to find another spot so I can prepare this area, the sunniest in the garden, for the native wildflowers I have coming in another week or so. My mind is in deep attention to each kick so the hedge will move well.

“Man, I used to live here forty years ago and there was so many rats here!” I stop and look over. His eyes are alive and kind. “You still have all the rats?”

“Well, yes, some,” I answer.

He barely listens, swept along in a memory. “The place, I mean, it was covered with rats.”

* * *

I carefully move the bush to the new hole I have prepared, swaddling the root ball, filling and firming the soil all around it.

“Excuse me,” a voice calls tentatively yet firmly from the open gate to the garden. “Can I?” They gesture into the garden with their phone pointed out in camera fashion.

“Of course,” I invite as pleasantly as I can muster. “It’s public space.” I return with a bucket of mulch and, kneeling, spread it evenly around the base of the plant, appreciating the scents.

“Thank you,” says a woman at the fence nodding and smiling. “The garden looks lovely.”

I stop and look up at her.

* * *

I was a suburban kid. My home filled nearly an acre of land and as I grew I took on its care – the mowing, the raking, the pruning, the pulling, the transplanting – forging a deep relationship. Among other things, this cultivated in me a feeling of connection, a two-way connection, that I continue to experience when I am in nature, and especially whenever I am working with nature. It is a relationship between myself and the plants, the animals, and the insects around me. It does not involve people.

* * *

As I walk back to the tool chest, I see that someone has widened the path that passes the small center island. It is crude work, disruptive, like a roadway widening project, the kind that levels trees, geometrizes terrain, and leaves a mess in the gaps it does not see.

Some years ago I planted a cluster of phlox in the island; they grew into a centering brightness. A blight got some of them, but around the same time, miraculously, one seeded itself and flourished at the edge of the island. The path-widener had removed it to where the dead ones had been, and I see it there now, wilting, stuffed hastily in a too-small hole, some of its roots groping confusedly into the air.

* * *

An older couple is chatting with one of the garden leaders, a friendly presence about the small space. As I busy myself with several other relocations, not wanting to be bothered, they gab away. At one point I must pass by them and my garden colleague stops me with a friendly smile and introduces me with gross yet flattering exaggeration (she’s really good at this) as the garden’s “expert horticulturalist.” We fall into talking. I learn that they volunteer in a garden down in the 80s. I apologize for ignoring them, explaining that my mind was in the dirt and the work, but, standing there with the three of them, suddenly this feels feeble. They laugh knowingly, and then I am laughing as well.

* * *

I arrive with a large box of native plants and set about what could be loosely and distantly conceived of as a kind of metaphorical restoration project. Into the box I smile a welcome to the milkweed, the bee balm, the fireweed, and the other plants. My daughter takes the box from me and gently places it on the path by the bed. I lift a fireweed plant carefully from the box, hand a trowel to my daughter, and begin to explain how to dig a hole.

* * *

Because my early relationship with nature was cultivated on land my family owned, with this relationship grew a sense that the nature there was mine. It occurs to me that in the back of my mind, as I regarded our little restoration, was the same sense of it as mine.

But the garden is not mine. This I have learned from the people who enjoy it and offer thanks (or who share wistful recollections of rats), and from fellow volunteers who disrupt and even destroy plants I have fostered in prior years. It is a painful process this learning, as much emotional as rational. It reworks my conceptions of my relationship to the nature and the people in this place, and what change might be possible here and in the patterns of relationship, resourcing, and action in the wider world.

It is difficult, but I am not pessimistic. For it may be that in the course of our at times abrupt interactions over different conceptions the others in our garden community are, in essence, learning too, experiencing – bit by bit – a transformation in their sense of care, especially of the nature there, and subtle shifts in their relationship with this little land we share.

Do you have reactions or thoughts about any of the themes in this piece? Shoot me an email here or use my contact page.

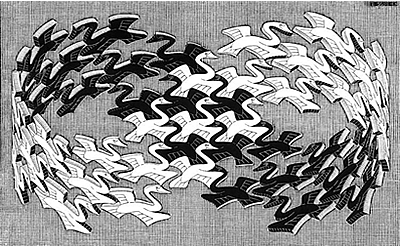

IMAGES: @ M.C. Escher; fair use. Photos of forest and gardening are copyright by Peter Szabo. All rights reserved. The wetlands photo is royalty-free.