Wild Hope

On February 2nd, Flaco made his escape. Someone damaged the enclosure of the Central Park Zoo’s Eurasian eagle-owl and he took flight. Experts and birders urged his recapture. After 12 years in captivity, and far from his native habitat, there was no way the great raptor (he has a 6-foot wingspan) could survive the “wild,” they said. But two weeks later the zoo called off its rescue/recapture efforts.

As was obvious from his pellets, and the testimony of birder-throngs, he was feasting on rats (Thank you, Flaco!) and other small mammals and doing just fine. He even has his own Twitter feed (@flaco_theowl). A recent post: “I’m not gonna waste my life, I’m LIVIN baby!” Wise words.

Smelling the Coffee

When I saw the State of the Chesapeake Bay 2022 Report in my inbox I thought of my father, an avid Bay sailor, and an image came to mind from sometime in the mid-1970s of him smoothing a Save the Bay bumper sticker on the car. But as I read on, this pleasant feeling did not linger…

For 2002, the Bay was rated D+. My daughter’s D+ on her math exam signaled serious trouble. There was, let’s say, a swift and effective response that included, among other things, penalties, technical assistance, and incentives “at scale.” Admittedly this problem of teenage teacher-alienation was of course far less complex than the problems plaguing the Bay watershed. Still, it offered a reference point for understanding how inadequate efforts to save the Bay have been.

According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, which prepares the report, the Bay’s raw score in 2022 was 32. A score of 40 might be obtained if the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint were fully implemented. At that level, the state of the Bay would be “improving.” With a score of 70, the Bay would be “saved.” We will never come close to 100, the state of the Bay at English colonization in the early 1600s. Pennsylvania, which causes the greatest share of damage to the Bay, lags far behind in its commitments. Earmarked federal funding is a fraction of what it needs to be. And the headwinds of climate change (increased stormwater, submerged marshlands, etc.) and land development continue to grow.

According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, which prepares the report, the Bay’s raw score in 2022 was 32. A score of 40 might be obtained if the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint were fully implemented. At that level, the state of the Bay would be “improving.” With a score of 70, the Bay would be “saved.” We will never come close to 100, the state of the Bay at English colonization in the early 1600s. Pennsylvania, which causes the greatest share of damage to the Bay, lags far behind in its commitments. Earmarked federal funding is a fraction of what it needs to be. And the headwinds of climate change (increased stormwater, submerged marshlands, etc.) and land development continue to grow.

In the nearly quarter century since the first State of the Bay Report the overall score has increased 5 points. With the current approach, and given the headwinds, could we seriously assert we will reach “improving” in 50 years?

The 2022 Living Planet Report from World Wildlife Fund offered an equally strong cup of Joe. WWF reported “a 69% decline in the relative abundance of monitored wildlife populations around the world [more than 5,000 species] between 1970 and 2018.” Landscape change — habitat fragmentation and destruction — is culprit #1, likely to be replaced in coming decades by the impacts of climate change. The world loses a Kentucky’s worth of forest every year. Every year.

The 2022 Living Planet Report from World Wildlife Fund offered an equally strong cup of Joe. WWF reported “a 69% decline in the relative abundance of monitored wildlife populations around the world [more than 5,000 species] between 1970 and 2018.” Landscape change — habitat fragmentation and destruction — is culprit #1, likely to be replaced in coming decades by the impacts of climate change. The world loses a Kentucky’s worth of forest every year. Every year.

This is getting to be an old story. But what is clear is that trying to accomplish our goals in the same inadequate way — over and over — won’t work.

The Bay’s challenges are not going to be met without major step-changes in action. To advance meaningfully on biodiversity conservation, WWF says we need “a move from goals and targets to values and rights, in policy making and in day-to-day life.”

Life on the Frontier

I’m going to get high-level conceptual on you for a moment to put the inadequacies, the required dramatic shifts, in some perspective. Bear with me.

Committed individuals and institutions make laudable and courageous efforts to bring about badly needed changes in our society. In our area of conservation and the environment there have been many great accomplishments. And yet, much of the time, lofty and excitedly articulated goals are not achieved.

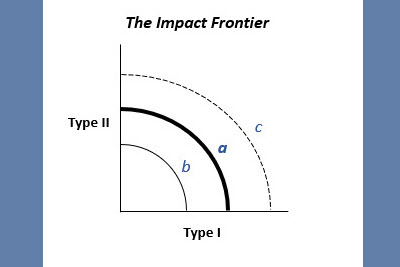

Funders and practitioners need to think more clearly, intensely, and pragmatically about what might be called the “impact frontier.” I know, sounds pointy headed. Take a look at the figure and let me explain.

The resources required to achieve impact — that constrain impact — fall into two overlapping categories. The Type I resource is simple and fundamental: money. Type II resources are non-financial, and they include things like ideas, laws, technology, volunteer manpower, relationships (including political influence), police and military force, and time, to name a few of the major resources that come to mind. (Yes, there are overlaps between Type I and Type II, but let’s stay at a high level for now.)

In the figure, the impact frontier (a) is the theoretical limit of what is achievable given the present state of resources. All too often we set goals (c) that lie impossibly beyond this frontier. They are not achievable given the state of the relevant resources. Not only that, most of the time we work inefficiently (b) and do not maximize the impact we could achieve up to the impact frontier.

In the figure, the impact frontier (a) is the theoretical limit of what is achievable given the present state of resources. All too often we set goals (c) that lie impossibly beyond this frontier. They are not achievable given the state of the relevant resources. Not only that, most of the time we work inefficiently (b) and do not maximize the impact we could achieve up to the impact frontier.

This clarifies two problems those looking to change society must address. The first is the gap between the wished for (c) and the theoretically possible/impact frontier (a). The second is the gap between what is theoretically possible (a) and what we are accomplishing today (b). You might say that the first problem is a problem of transformation, while the second is a problem of optimization.

The only solutions to these problems — the only ones — are these:

1. to make our goals more practical, that is, to better fit them to the current state of relevant resources (shift c to a);

2. to do a much better job maximizing use of the resources available (shift b toward a) – e.g., by resolving organizational dysfunction, working smarter or better, setting priorities, etc., or

3. to fundamentally change the state of relevant resources (shift a to c) — e.g., radical increases in financial resources, enactment of landmark laws, groundbreaking changes in thinking, etc.

#1 and #2 require courageous leadership, sober choices, and often wrenching institutional change. Solving these management problems, problems of optimization, is essential for making the sector more effective and more widely relevant and credible.

And yet, to solve climate change, to solve the biodiversity crisis, to solve even the problems of the Chesapeake Bay, we need transformative changes in financial resources, mindsets/thinking, law and policy, etc. (#3) We need to shift (a) to (c) and beyond. In my view, the magnitude of the needed impact-curve shift will not happen without much more aggressive action.

Accelerating Civilization

(Transformation: Shifting out from a to c)

In 1932, Albert Einstein, chairing a League of Nations committee engaging the century’s greatest minds on the world’s biggest challenges, wrote Sigmund Freud for his thoughts on how humankind might bring an end to war. Freud responded mostly with eloquent pessimism. Even so, toward the end of his letter he offered the cautiously hopeful notion that advances in civilization, in human culture, might, over time, produce this result. I wonder if we asked him how the war on nature might be brought to an end whether Freud’s response might not have been the same. After all, it’s just another form of war on ourselves.

But how to advance civilization? How to accelerate that advance? From the perspective of the impact frontier, how to shift that damn curve out to where it needs to be?

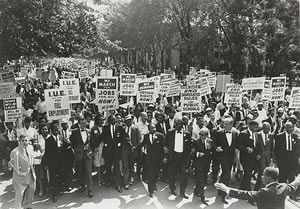

I encountered one reference point recently while reading Bayard Rustin accounts of his experience of two crucial moments in the Civil Rights struggle: the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

On Sunday, February 26, 1956, in the midst of the bus boycott, Rustin reports that Martin Luther King told his packed church:

We are concerned not merely to win justice in the buses but rather to behave in a new and different way – to be nonviolent so that we may remove injustice itself, both from society and from ourselves.

With these words, I was struck afresh by the singular courage of those who sat calmly at the receiving end of society’s violent discomfort, by the great costs to those who faced death for their speech and activity.

Direct action accelerated the advance of civil rights by many years. Nonviolence was the DNA of the approach. Transformation, not simply of laws but of behaviors and mindsets, of souls even, was the standard of success.

Direct action accelerated the advance of civil rights by many years. Nonviolence was the DNA of the approach. Transformation, not simply of laws but of behaviors and mindsets, of souls even, was the standard of success.

What is our analogue today?

This question brought to mind Andreas Malm, the Swedish academic and climate activist who is outspoken in his critique of capitalism and its responsibility for climate change, and for his urging sabotage of CO2 emitting infrastructure. (Though as he told David Remnick on the New Yorker Radio Hour, “I am in favor of destroying machines, property — not harming people.”)

Taking the opportunity to reflect more broadly about Malm’s ideas on the release of his most recent book, White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism, James Butler wrote, “It was once possible to believe that climate change might produce rational, meliorist, collectively-minded solutions. The last thirty years… should have disabused us of this notion.”

While uncertain of the specific path ahead, Malm appreciates the level of intensity it will involve. “A transition will happen through intense polarization and confrontation, or it will not happen at all.”

When it comes to certain questions — the health of Chesapeake Bay, the abundance of biodiversity, the changing climate – we have run out of one of the more potent “Type II” resources, time. The tactics of the past, however functional, produce impact at too slow a rate, when they produce it measurably. What’s needed is a disruptive advance. Looking to the civil rights movement for inspiration, for these are moral questions and not simply instrumental ones, the need for nonviolent direct action — to change minds, to change culture, to advance the civilizing influence — seems clear: redoubled, more intense, utterly nonviolent (the source of the moral force). For this to happen, funders need to place urgency at the forefront of their criteria and let go of concerns about wave making. Waves are what we need. Waves are what we need.

Two Nickels

(Optimization: shifting from b to a)

Long wished for by the community garden I volunteer in, the gazebo finally arrived last fall. And then through winter it sat in pieces across the garden, awaiting rescue. With the parsimonious mindset of the low-capacity organization that has barely two nickels to rub together, the garden committee had only looked so far ahead, assuming the rest could be accomplished with volunteers and good intentions. A call went out to help assemble the structure. But on the appointed day, it was raining, and the raising was canceled. Did someone know a contractor who might do it cheap? One got lined up, but he developed medical issues and faded away. There was a long fallow period during which even the gates of the garden were uncharacteristically locked.

And then at last, movement. Priorities were set, a rarity. Scarce dollars were paid to the Amish supplier who’d delivered it. Voilà, gazebo!

There were consequences. Many other desires are now necessarily delayed. But rather than continuing to try to move all things forward with aching torpor, one big, concrete thing was accomplished. And with the gazebo a reality, new programs and events, new levels of engagement, are possible.

With Gratitude

February marked 25 years since I founded Bloomingdale Management Advisors. From those early days helping The Nature Conservancy plan for and launch the David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellowship, and then helping David begin to flesh out his foundation, I have been enormously fortunate to partner with many extraordinary people striving to advance the condition of nature across the U.S. and around the world. I am grateful for the deep and honest thinking we have done together, for the organizational complexities we have navigated, and for the fun and the impact we have had so far.

February marked 25 years since I founded Bloomingdale Management Advisors. From those early days helping The Nature Conservancy plan for and launch the David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellowship, and then helping David begin to flesh out his foundation, I have been enormously fortunate to partner with many extraordinary people striving to advance the condition of nature across the U.S. and around the world. I am grateful for the deep and honest thinking we have done together, for the organizational complexities we have navigated, and for the fun and the impact we have had so far.

Thank you!

Flaco photo by Rhododendrites. Gazebo by Peter Szabo. All other photos in the public domain.