Work Re-Worked

“This going to an office 9-to-5 thing is ridiculous,” our son complained over dinner not long after starting his first post-college job. Our response – Get used to it – was rigid and hopelessly out of touch.

Fact is, Covid has reworked the structure of work-life. Those who could retreated home. The work got done. Most folks are resisting returning to offices. Top managers used to the old ways are confounded.

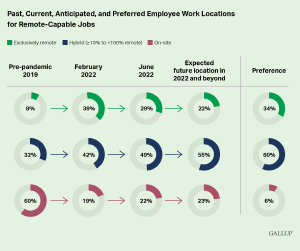

A recent Gallup poll offers some striking facts. Highlights include:

- Relatively few people with “remote-capable” jobs are presently on-site full time (20%). Only 6% want to be entirely on-site in the future.

- Hybrid work continues to increase. 60% say they want hybrid arrangements in the future.

- The share of people saying they are extremely likely to change jobs if not given more flexibility has grown substantially since June 2021 across every category of worker – remote-only, hybrid, and on-site.

- Hybrid is here to stay. Employers must adapt or risk losing talent, both younger and older.

Even as the recognition of the need to change has dawned, organizations are struggling with how to do so. Gallup offers a few nuggets from additional research into hybrid work arrangements (which seem destined to predominate):

- Coming into an office should have an obvious and significant value to it. “A policy is not an answer to why people should come to the office,” Gallup concludes. (The general values are cohesion, culture, and creativity. To me, the challenge is to design meaningful structures and events/interactions that advance these values.)

- The success of flexible work arrangements requires, in part, increased communication by managers and among teams about priorities and tasks, and the setting of clear expectations “about when employees are and are not expected to be available.”

- Across hybrid work teams (some people virtual, some on-site), virtual is the least common denominator. If some people are virtual, to the extent everyone behaves virtual – i.e., on-site staff “bringing laptops to all meetings so everyone has an on-screen presence” – the work environment feels more engaging to everyone.

Two months in, our son became eligible to work from home one day a week. He jumped at it. He and his cohort sort out the day each will take. The work gets done. I’m not sure it’s as liberating as he’d like, but he seems less alienated, more energized. “I’d never take another job that didn’t have flexibility,” he said the other day. If his declaration indicates something general about twentysomethings, employers be warned.

Smarts, Seasoned

The Denver Broncos lost a heartbreaker to the Seattle Seahawks on the opening Monday night of the National Football League season. For aficionados there were many captivating storylines: the return of Russell Wilson (Denver’s recently signed “franchise” quarterback) to Seattle chief among them.

While that had entertainment value, the story I want to foreground here involves the way the game ended. Ball on the Seattle 46, fourth down and four yards to go, about 30 seconds remaining in the game, Denver down by 1 point. Russell Wilson is one of the best quarterbacks in the NFL. But Denver coach Nathaniel Hackett decided to send in his kicker to try a field goal of 64 yards, among the longest ever attempted. The kicker missed wide left and howls over Hackett’s decision erupted.

At his Tuesday morning news conference, a contrite Hackett said that his decision had been a mistake. In explaining the decision, he said that his management team’s intensive game planning included numerous scenarios for a game-ending drive and fourth down situations. They concluded that if they advanced the ball to the Seattle 46-yard line they would kick.

As the dust of immediate recriminations settled, two takeaways with broader application struck me.

One was the importance of forethought – detailed planning, including scenario planning. If running an operation like a 60-minute football game takes the intensive planning Hackett alluded to, surely running even a moderately complex organization year-to-year requires at least as much.

The second takeaway is the value of experience and judgment. This is Hackett’s first year as a head coach. What will come with experience, as seasoned managers understand, is situational judgment. The plan reflects informed and deliberative choices and must guide the institution. But departing from the plan can, at certain junctures, contribute to organizational success. The judgment to make this decision in game-on-the-line moments grows truer and surer with experience.

Hackett’s experience this season may provide an interesting case study in leadership development. We’ll keep an eye on him and see what we can learn.

Big Lessons from a Small Place

Quail Call’s arrival in my mail box always brings delight. Its mix of information and research insights for hunting-land managers and owners (the quail hatch report, best practices in hunting-dog training, etc.) fascinates me, suburban-born and now city-dwelling. It also brings to mind the profound beauty of a longleaf pine-wiregrass landscape.

Quail Call’s arrival in my mail box always brings delight. Its mix of information and research insights for hunting-land managers and owners (the quail hatch report, best practices in hunting-dog training, etc.) fascinates me, suburban-born and now city-dwelling. It also brings to mind the profound beauty of a longleaf pine-wiregrass landscape.

Often technical and seemingly of somewhat narrow relevance, frequently the little publication, put out by Tall Timbers, a preeminent research and conservation organization set among the longleafs of Georgia and Florida, offers insights for conservation across the country. A recent study is a case in point.

In “Quail Management Provides Many Ecosystem Services,” Tall Timbers researchers Kevin Robertson and Cinnamon Dixon summarize the results of their research into the ecosystem services provided under several land management regimes in the Red Hills of southwest Georgia and northwest Florida, including, among others, row-crop agriculture, restored pine savanna managed with fire, and native land (that is, undisturbed pine savanna).

To me, the headline finding was the extremely long time it takes to restore land after it has been disturbed by row-crop agriculture – even with the reintroduction of natural processes like fire. According to the study, 75 to 100 years of fire use yielded significant gains in native plant species richness (which drives the population of insects and the animals that depend on them) and soil health. But even then, the level of ecosystem services does not reach that of undisturbed, native land.

This says three things of note that people involved in land protection and conservation broadly already appreciate but which bear reinforcing – with some volume – for a general audience:

- We need to prioritize protection of undisturbed wild lands. As the authors put it in refreshingly understated terms, “Given that native pine savannas generally had the highest levels of most ecosystem services, prioritizing them for protection from intensive soil disturbance is a good idea.” Indeed.

- We need more and better stewardship. Too often, land is protected but then not cared for. Quality stewardship is essential for healthy soil, water, and natural diversity. Society needs to dedicate more resources to it.

- We need to take a long-term perspective. Of some hope is the finding that, while it may take a century, if we reintroduce natural processes to the land natural diversity can be largely restored. Policy, plans, and practice should reflect this.

Fire Sage

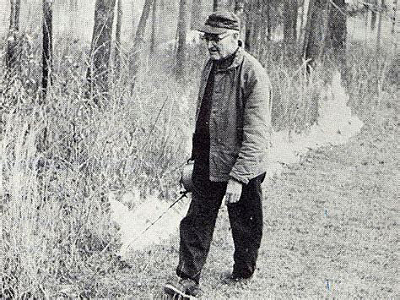

With Tall Timbers come to mind, I want to make another point for managers. Tall Timbers’ culture has grown in good part from the work and philosophy of Herbert Stoddard, who helped found the place in 1958.

A great friend and colleague of Aldo Leopold (among other things, they helped found The Wildlife Society in 1937), Stoddard was a genius whose lesser fame is perhaps due to his being even farther ahead of his time. His work centered around the holistic, long-term balance between natural and commercial outcomes in the management of land – what we now call sustainability.

Stoddard placed supreme value on experience over theory. Don’t get me wrong. He read the current scientific literature, participated in debates. But in fashioning his method he privileged what he learned through his experience in the field.

Stoddard emerged from his late-1920s research into the decline of bobwhite quail in the Southeast for the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey (which in time would become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) convinced that reintroducing fire (long practiced by Native Americans and, later, small farmers) was the key to revitalizing the local ecology. This was a profoundly provocative idea in the context of a national government and forest products industry completely dedicated to the suppression of fire. But he had seen it in practice, tested it. He trusted his experience and his mind.

Stoddard provides an excellent reference point on management. Take note of the science, of the literature on management, philanthropy, or whatever might be your work, but privilege what you know and the uniqueness of your circumstances.

In a talk on the use of fire he gave late in life, Stoddard made a broadly resonant point about the role of circumstance. It may emphasize too much the importance of tailoring everything to circumstance, but if there’s an exaggeration, it helps highlight the general message.

Ever since I was interested in burning we had to make that decision on the basis of the land you were standing on. You can’t possibly give a formula for burning on land you haven’t seen. You have to go and visit a piece of land and see what it requires. You have got to apply it just as you would in cutting timber. You can’t say you are going to cut ten percent or twenty percent of a hundred thousand acres. You’ve got to go and examine that land and somebody that knows what he is doing has got to do the work. And that’s where the art comes in. Science is never going to solve that. This would be the art.

Growing Consensus

My community garden is more “community” than “garden”. Yes, we have a piece of ground where flowers, shrubs, fruits, and vegetables are tended. Yes, ours is a public area with benches and tables and chairs in a setting of trees and plants. We check those Merriam-Webster boxes for a garden. But the garden is set within a broader community and it is cultivated and managed by a closer-in community of volunteers. The dynamics of this latter community and how it makes decisions is of particular interest to me.

While garden-tenders share a passion, we don’t always share points of view. A minor action someone has taken – planting a new plant, pruning a shrub – may spark lively disagreement, but the community still functions. However, when there is a decision of significance to be made, the tendency in our not-very-rigidly-governed group is to seek a kind of sufficient consensus.

The informality of this process can be maddening (each of us has been exasperated at times), but its organic-ness has a distinct beauty. Through the sharing of ideas, side conversations, the occasional group meeting, gossip, and other interactions a collection of views emerges and seeks to coalesce around a rationale into a more-or-less collective viewpoint. Sometimes a viewpoint emerges and holds, sometimes it does not, sometimes it moves between these states until it holds, or doesn’t.

The raised bed is a case in point. Straight down the center of the part of the garden that gets the best sunshine runs a concrete slab just a few inches below the surface. Nothing I’ve planted there has worked sustainably. So early this year I floated the idea of building a raised bed (see a typical plan above). The rationale was that greater soil depth would enable us to grow native plants more successfully. But this reasoning did not attract consensus. People worried what the structure would look like, whether it might feel out of character with the rest of the garden. I did not press the idea.

Some months later anxieties arose about the possibility that our soil was contaminated with lead. More children were now playing and working in the garden, making this an even greater concern.

I nudged the idea forward again, but along a new path. We could construct a raised bed, prepare and fill it with clean soil, and make it a children’s area, perhaps even plant some native plants and learn more about pollinators. This reasoning produced a lively and linking energy throughout the group. Within weeks a load of wood for the bed arrived.

A simplistic takeaway is that a rationale based on human benefits always beats one based on benefits for nature. A more valuable one is the importance of staying attuned to the community’s thinking and feeling, and exerting energy as opportunity appears.

Yet even this is a bit instrumental and too focused on the individual. In the garden, a rich interplay continuously unfolds between individual and community. The bigger outcomes reflect the will of the community, as surfaced at times through the actions of an individual, who, consciously or not, may well be the instrument of the community.

The community is alive and dynamic. We’ll build the bed and see what unfolds from there.